There were times in American history when businessmen ran the government. Spoilers: it didn’t go well. One of such situations occurred after King James I granted a charter to the Virginia Company of London in 1607. The Virginia Company was not a company in a modern sense; rather, it was a bunch of companies and private entrepreneurs united to explore and exploit whatever they find in the land of Virginia. American historians often don’t bother themselves with the Virginia Company (if you decide to read more about it, there will be a lot of E-Z borrowing (and giving up)) – after all, it only functioned for 17 years until it was dissolved by the royal order since the venture turned out to be almost a complete failure.

Indeed, the members of the Company probably did not look as confident as in Disney’s Pocahontas movie:

For glory, God and gold and the Virginia Company!

The riches they hoped to find in the Virginian soil were not there, and the hopes for the lucrative trade with the locals proved futile. The tobacco they planted thank to John Rolfe’s (newly born) agricultural skills were worse in quality that Spanish product and King James had to be persuaded to grant Virginia some kind of monopoly on selling tobacco to England. Sounds bad, doesn’t it? Wait, there’s more!

Virginian planters were so devoted to growing tobacco they neglected the production of food for themselves and had to rely on Indians and the supplies from England. The latter task was the job of one of the smaller companies in Virginia’s bunch: the Magazine. Indians were not always willing to trade with the colonists, and the Magazine occasionally appropriated more money from the treasury that they were owed.

As if it wasn’t enough, Powhatan Indians also massacred some colonists on March 22, 1622. Colonists had to abandon their plantations and get crowded to be able to defend themselves. Safety and food was their primary concern, and they begged the Virginia Company to help them handle these two pressing issues. The response was clear: your primary concern should be growing tobacco [1].

Since it was as bad as it sounds, the members of the Virginia Company started looking for the culprit, which in the hierarchy-oriented minds of 17-century Englishmen was the leader. But which leader was it – Sir Thomas Smith who led the company until 1619 or his successor Sir Edwin Sandys?

Candidates for the culprit. Edwin Sandys (left) probably looks eviler than Thomas Smith (right), but some people in the Virginia Company didn’t think so.

The true answer is: we don’t know, and neither did King James. Quarrels between various leaders of the Company and Virginian planters soon turned into an endless stream of petitions and proposals destined to bury the king’s desk under their weight. Alderman Johnson claimed that nothing but tobacco was produced because of Sandys. Captain Bargrave made the same complaint but blamed it on Smith. Planter John Martin asked the king to kick the Virginia Company out of Virginia. Nathaniel Rich begged James to investigate the manipulations of Sandys.

At some point, James finally had enough. In an unusually short note, he asks the House of Commons to follow his example and stop reading this gossip material [2]. Soon, the Virginia Company was dissolved.

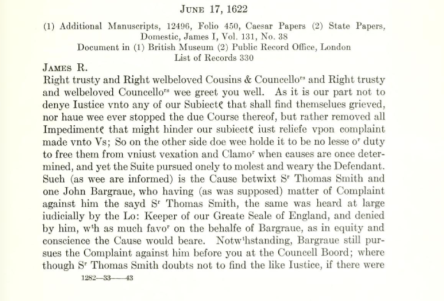

This is how king James normally talks [3].

And this is how he talks if you drive him crazy [2].

We don’t have to pick between Smith and Sandys. The very thought that all these plan-producing, quarreling leaders were staying in London, perhaps never even seeing Virginia, can be eye-opening. It took 9 weeks to get from the Chesapeake Bay to England and 6 weeks for a reverse trip (thanks to a handy current). What adequate response could the leaders provide to the colony’s problems given the very limited powers of the Virginia governor?

In any case, it was the Virginia Company who failed, not the Virginia settlers. Those continued growing their tobacco and, as it would become clear in 1776, preferring to be ruled by people who are actually from Virginia.

Sources: