This post is an excerpt from Justine’s award-winning article in Villanova’s interdisciplinary graduate school journal Concept. She will be continuing her research on this topic during the summer with funding from the university.

You can find the full article at: https://concept.journals.villanova.edu/article/view/2275

by Justine Carré Miller (@carrejustine)

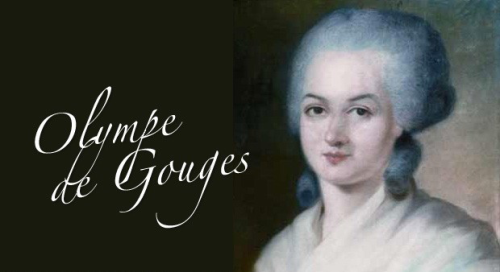

I first heard the name Olympe de Gouges in an undergrad French History class, when studying the French Revolution. In August 1789, when the recently formed National Assembly wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Men and of the Citizen, comparable to the U.S.’ Declaration of Independence, its rights solely applied to men; women did not enjoy the benefits of the French Revolution’s ideas of freedom, democracy, and natural rights. It is in this context that Olympe de Gouges’ name and writings came up. Frustrated by the government’s refusal to acknowledge women’s rights, De Gouges wrote and published her own Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen in 1791, modeled on the original declaration. In a later class I took about the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, she was again mentioned very briefly. While I personally found the issue of women’s rights during the Revolution fascinating, it seemed to me that in my classes it was always overlooked to focus on other major events. It wasn’t until I took a graduate seminar about the French Revolution last fall semester, that De Gouges’ Declaration was assigned to read and that the question of women’s rights was discussed. I decided to write my term research paper on her and I soon realized that besides her Declaration – her most famous text by far – De Gouges had written many texts prior to and during the Revolution to advance the cause of women’s rights and gender equality. Not only that, but she also supported marriage reform, the right to divorce, the abolition of slavery, the recognition of illegitimate children, and social projects such as medical clinics for women. While De Gouges’ revolutionary texts were written in the form of political pamphlets or posters, her texts written before 1789 were mostly plays.

I decided to do research on her plays as a means of advocating social reforms, and I faced some challenges. The first one was that Olympe de Gouges has for a long time been ignored or purposefully left out of the narrative of the French Revolution. While it is easy to find biographies of Louis XVI or Robespierre from as early as the 1800s, the earliest book I found about her dated from the 1980s. The reason for this is that during and after the Revolution, De Gouges was considered an extremist, not necessarily for her political ideas, but because she was an outspoken woman. She was absent from dictionaries and history books, her texts considered irrelevant, and not worthy of study from a literary standpoint. Therefore I couldn’t find literary analyses of her texts either, and her plays were only mentioned in more recent historical articles. As far as her actual plays are concerned, it was equally hard for me to find the complete texts. Unlike recognized great works of the French Revolution, they were harder to access, not available online or in the library. For some of the plays, I had to find the original publication manuscripts, published in 1788.

Once I had gathered and read a significant number of her plays, some themes in her writing became obvious, two among them which interested me the most were the reform of marriage and the right to divorce. After a close analysis of the plays in which these themes appear, I noticed two important things: first, how subtle and accessible her advocacy for reform is in her plays, contrary to her later texts; second, how the ideas put forth in her plays relate to her own life experience and fit in with her later Declaration.

In the six plays that I studied for this research paper, each of them features female characters who by the end of the play were either able to overcome the oppression they were a victim of, make their own life decisions, or significantly improve their living situations: in The Necessity of Divorce, wife and husband are reconciled, and the wife is the morally superior one in the relationship; in The Forced Vows the main character is able to marry the man she loves instead of being forced into a convent; in Black Slavery, the women of the plays assume the dominant role in their relationships and resolve a local government crisis; in Molière visits Ninon, the main character escapes a forced marriage and marries the man she loves; in The Unexpected Marriage of Chérubin, the main character, of modest background, also escapes a forced marriage, finds her parents, is recognized as an aristocrat, and marries a Marques; and finally in The Corrected Philosophe, the wife overcomes accusations of adultery and is reconciled with her husband. In these plays, De Gouges depicts strong and independent women, who are morally superior to men, as well as non-traditional relationships and gender roles, to advance the causes for egalitarian marriage as a social contract based on mutual feelings, and for the right to divorce. Not only are all these ideas reflected in De Gouges’ Declarationpublished a couple years later, but they are also based on her own life. As was common in Early Modern France, De Gouges was subjected to an arranged marriage when she was only fourteen to a man she despised and when she was widowed, she refused to remarry so she would never be subjected to a man again.

While she stood out because she was a woman activist, De Gouges’ ideas were not groundbreaking since thinkers of the Enlightenment had been writing about marriage and divorce throughout the 18thcentury. In addition, De Gouges’ texts, both her plays and her later political texts, were not widely spread nor did they influence the decisions of the Nation Assembly regarding marriage reform. However, as historians Darline Gay Levy and Harriet B. Applewhite have argued, “the political language and the acts of women in the revolutionary capital [of Paris] – their political performances – cannot be dismissed simply because the implications of these words and deeds were not realized in French revolutionary politics…Rights claimed, once defined and defended, become imprinted in a political culture.” Even though De Gouges’ writings did not result in the passage of specific laws or of women’s citizenship, she participated in the creation of a liberal tradition in France.