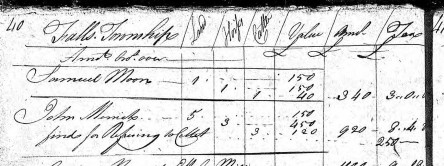

(pictured above: John Merrick’s written protest of his tax fine)

By Sarah Marcinik

I first became acquainted with John Merrick last summer. My research on slavery in Bucks County, Pennsylvania had led me to skim a decade’s worth of tax records from the 1780s, looking for entries on slaves. In the process, I stumbled upon a taxation issue of a different sort. In the records for 1785, a solid block of text, in sharp contrast to the prosaic rows and columns surrounding it, started out at me. “John Merrick,” it read, “says he is not Represented & therefore will not give in any Return untill [sic] such times as he is Admitted to vote for Representatives of Assembly and bids me aquaint [sic] the Commissioners of the same.”[1] I was elated to have apparently discovered a very personal case of that well-known motto, “No taxation without representation!” But as I investigated John Merrick’s case by looking into the Pennsylvania voting laws, I could find nothing that would easily explain his disenfranchised position. It is only in my recent researches, turning to other sources, that I believe I have finally solved the mystery—and the result is not what I expected.

My research on John Merrick has not been comprehensive, but there seems to be only enough records of him to make a slight biography. Merrick appears regularly on the Bucks County tax assessments between 1778 (the earliest record I have found for the county) and 1793. These records show that he was a tanner and a longtime resident of Falls Township in Bucks County. He was usually assessed for a small parcel land—between four and six-and-a-half acres—with a house, a few livestock, and his own tanning yard. In a few years there are some additions, such as two indentured servants in 1782, and a “riding chair” in 1786 and the years following.[2] While Merrick was obviously not rich, he appears to have been able to keep up a modest livelihood.

I initially thought that Merrick’s economic circumstances were the obstacle to his ability to vote, but this assumption was complicated by my investigation into Pennsylvania’s voting laws. In fact, when Merrick made his protest, Pennsylvania was about the last place in the fledgling United States where a man of even his modest status would have been barred from voting. The state was the earliest and most aggressive in allowing more men to vote than had enjoyed the privilege under the colonial administrations.[3] Pennsylvania’s 1776 Constitution had declared that “Every freemen of the full age of twenty-one Years, having resided in this state for the space of one whole Year…and paid public taxes during that time, shall enjoy the right of an elector.”[4] No property qualifications were stipulated.[5] Applying these qualifications to John Merrick’s case offers little hope for explaining his situation. His appearance on the tax records indicates that he was free, had come of age, and had been a resident for well over a year.

The requirement of paying taxes seemed the only reasonable obstacle to Merrick’s ability to vote. However, while my research shows that his tax records were somewhat complicated, there was no conclusive evidence that taxes were the problem. The tax records I have examined for Bucks County are rather jumbled, making it difficult to positively identify whether or not an individual paid taxes every year. From what I can tell, Merrick may have been absent from the tax assessments for a few of the years between 1778 and 1793. However, the fact that he has essentially all the same assets after one of these gaps as before suggests that the issue is missing data or another error, not that he lost all his taxable property and therefore did not pay taxes. If some fluke such as the latter did occur, it would be difficult to confirm, and overall seems improbable. However, there are two verifiable irregularities in Merrick’s tax records. In his record identified for 1779, there is an added line that appears to read something like “Fined for refusing to collect,” and in the following year his evaluation is marked “No return.”[6] It may be that Merrick also refused to pay taxes in these years, though without making as formal of a protest. Despite missing entries and tax problems, the overall impression Merrick’s tax records give is that it was probably not economic considerations or tax issues that kept him from being able to vote.

(Merrick’s fine)

In fact, it is the records I paid the least attention to that have come to be the most important in understanding the mystery of John Merrick. In my research, I came across his name in Bucks County Quaker records.[7] Though there appear to have been multiple John Merricks in Bucks County, some of these records are from Falls Township, suggesting that they refer to the John Merrick in question. Secondary sources helped me to see that Merrick’s being a Quaker was, in fact, vital to the mystery. Voting in Revolutionary America explains a voting law I had little considered—the test laws: “At the beginning of the war, most of the states adopted statutes requiring individuals to sever all connections with England and declare their loyalty to the American cause. Those who refused to take this oath of allegiance were often denied the vote.”[8] Pennsylvania was one of these states, with test laws in effect between 1777 and 1786.[9] It was these laws, I believe, that prevent John Merrick from voting—but not because he was a loyalist. My suspicions were aroused, and I was finally able to confirm them with another source: “Quakers are forbidden to take oaths, and although other states were flexible with their Quaker citizens in terms of their Test Acts, Pennsylvania was not.”[10] If John Merrick was a Quaker, then, whatever his political beliefs, he could not take the oath, and therefore would have been barred from voting. This, I believe, is the answer to the mystery of John Merrick and the vote.

In the end, John Merrick’s “no taxation without representation” is very different from the one we are familiar with, but no less valid. While situations like his are undoubtedly known to some scholar, it was new to me. Though I did not find what I expected to on this research journey, I am still intrigued by the man who dared to return a protest rather than a tax payment because the law inhibited him, as a Quaker, from voting. It is some consolation to know that the year after Merrick made his protest, the test laws were removed, therefore hopefully allowing him to vote. The case of John Merrick may not be the familiar story, but it is nonetheless a real and perhaps vital part of the story of the Early Republic.

Sources and Further Reading:

1790 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. No URL.

Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Tax Records, 1782-1860 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. No URL.

“Constitution of Pennsylvania—September 28, 1776.” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School. C. 2008. Accessed April 28, 2019. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/pa08.asp.

Pennsylvania, Tax and Exoneration, 1768-1801 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. No URL.

Pennsylvania, U.S. Direct Tax Lists, 1798 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. No URL.

Proprietary and Other Tax Lists of the County of Bucks (Pennsylvania Archives, Third Series, Volume Thirteen). Ed. William Henry Egle. Harrisburg: William Stanley Ray (State Printer of Pennsylvania), 1897. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x030224058.

State of the Accounts of the County Lieutenants During the War of the Revolution. Ed. William H. Egle. Harrisburg: Clarence M. Busch (State Printer of Pennsylvania), 1896. https://catalog.hat hitrust.org/Record/003239509.

The Statutes at Large Of Pennsylvania From 1682 to 1801, Vols. 8-12. Harrisburg: William Stanely Ray/Harrisburg Publishing Co, 1902-1906. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002 030316.

U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. No URL.

Doyle, Robert. “Habeas Corpus: War against Loyalists and Quakers.” In The Enemy in Our Hands: America’s Treatment of Prisoners of War from the Revolution to the War on Terror. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jcngh.8.

Dinkin, Robert J. Voting in Revolutionary America: A Study of Elections in the Original Thirteen States, 1776-1789. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982.

[1] Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Tax Records, 1782-1860 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. The spelling and punctuation is original as far as I can make out.

[2] For Merrick’s tax records, see Buck County Tax Records.

[3] Robert J. Dinkin, Voting in Revolutionary America: A Study of Elections in the Original Thirteen States, 1776-1789 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982), 32, 36.

[4] “Constitution of Pennsylvania—September 28, 1776.” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School. C. 2008. Accessed April 28, 2019. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/pa08.asp.

[5] Dinkin, 32.

[6] Pennsylvania, Tax and Exoneration, 1768-1801 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. I did not find these years marked on the digitized records, but the Ancestry.com database identifies them as 1779 and 1780.

[7] See U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935 [database on-line]. Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

[8] Dinkin, 43.

[9] Dinkin, 43.

[10] Robert Doyle, “Habeas Corpus: War Against Loyalists and Quakers.” In The Enemy in Our Hands: America’s Treatment of Prisoners of War from the Revolution to the War on Terror (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010) http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jcngh.8, 44.