by Kelly Murmello (@kellymurmello)

In August 1952, my father was nine years old and the oldest of three children, when his family moved into their brand-new home in the Stonybrook section of Levittown, PA. They were one of the first families to move into what would become a model of suburban life across the country. Like many “Levittowners,” my grandfather was a World War II veteran, who moved from the outskirts of Philadelphia. With the return of so many veterans, suitable housing was in short supply. My grandparents not only wanted more space and their own yard, but an idyllic community and a better life for their children. This is exactly the dream Levitt Builders was selling with their newly planned community in the town named after them. However, the dream was not meant to be available to everyone. African Americans were explicitly excluded from the community. The Myers family, seeking the same opportunities as my own family, would bring the Civil Rights movement to this Philadelphia suburb in the summer of 1957.

(The identical living rooms of the Myers family and my father’s family. Explore PA; Hoare family photo collection)

The World War II veteran population and their families was exploding in the region. Many were lower-middle class with little more than a high school education, but new factories and industrial jobs in the Fairless Hills area attracted a huge number of returning soldiers looking for work. William J. Levitt capitalized on the housing need in the area, buying up 5500 acres of farmland, and eventually building 17,311 homes. With planned shopping centers, community pools, parks, churches and schools, Levittown was the neighborhood that many young Americans had dreamed of. The modest, assembly line homes sold with very little down, and qualified for GI Bill benefits and Veterans Affairs financing programs.

This prototype of the new suburbia came with a set of rules, covenants, and deed restrictions in hopes of maintaining property values. Homeowners agreed not to change their homes’ paint colors, could not hang wash out to dry on Sundays, and could not put up fences on their property. Like most new building developers dependent on FHA loans, Levitt Builders kept African American families out. William Levitt was very open and transparent about his stance on selling to African Americans, stating:

“The plain fact is that most whites prefer not to live in mixed communities. This attitude may be wrong morally, and someday it may change. I hope it will. But as matters now stand, it is unfair to charge an individual for creating this attitude or saddle him with the sole responsibility for correcting it. The responsibility is society’s. So far society has not been willing to cope with it. Until it does, it is not reasonable to expect that any one builder should or could undertake to absorb the entire risk and burden of conducting such a vast social experiment.”

Although Levitt refused to sell to African Americans, he could not prevent owners from reselling their properties to whomever they chose. Five years after the first families moved into Levittown, a new family, The Myers, moved in to the Dog Hollow section of Levittown, in Bristol Township in August 1957. With two young children, and another on the way, the family needed a larger home and Mr. Myers had recently taken a job with a local company as an electrical engineer. For the first few days, Bill and Daisy cleaned, painted and fixed up their new home in preparation for their two young children to move in. Many neighbors saw the couple coming and going, assuming them to be hired workers. When the mailman stopped by the home with a package for delivery, he asked the woman who answered the door if he could speak to Mrs. Myers, the new owner. The woman who answered the door informed him that she was, in fact, Daisy Myers. The mailman promptly proceeded through the neighborhood shouting to everyone who lived there, “It’s happened! N****** finally moved to Levittown!”

Hostile neighbors assemble around the Myers home (Explore PA)

Hundreds of people appeared in the street outside of their home. Neighbors shouted vulgar names at them, told them to get out, and threw rocks at the home breaking their picture window. Protestors stood in front of the house day after day. Crosses were burned on neighbors’ lawns that tried to help the family or were thought to have provided them with goods and services. Several neighbors rented a vacant property behind the Myers’ home, where they flew a confederate flag and blasted loud music with racist undertones. The local Bristol Township police were unable (or unwilling) to control the crowds. Several neighbors (including some that were occupying the vacant home next door) started a group called Levittown Betterment Committee, comprised of approximately 600 people. They circulated petitions throughout the Levittown neighborhoods to protest Negros in their “closed community.” The committee claimed that an influx of colored families would increase crime, lower property values, and force whites from their homes.

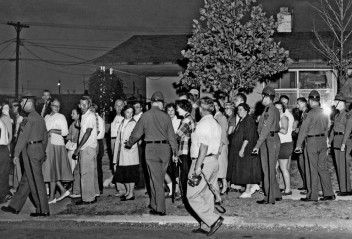

State police dispersing Levittown citizens from in front of the Myers family (New York Times)

The Myers family appealed to the Pennsylvania Governor and the state Attorney General for assistance. Governor George Leader ordered the State Police to control the mobs. By August 24th, the rioting had decreased, but the confrontation was not over yet. When a group began hurling rocks at the officers, giving one a concussion, the protestors were pushed back by the State Police. Individuals later claimed the officers used “Gestapo methods” against those who opposed the “invasion” of their community by the Myers family. After several tense days, order had been restored and the Myers family was able to live in relative peace. They would continue to reside in their Levittown home until 1961.

Myers family friend and neighbor Lew Weschler, whose home was also targeted (Forward.com)

In later interviews, Daisy Myers continually said that she liked to remember the good part of those days rather than focus on the ugly evil of some. She reported that many of her white neighbors would help clean up after night riots, offered to help her shop or watch the children, and stood guard to protect her and her children while Bill was at work. In 1958, Levittown’s second African American family moved in, the Mosbys. The family’s daughter Theresa, spoke with The Lancastrian in 2007 to recall her experience. Although the family was largely left alone when they moved to the neighborhood, Theresa faced racist attitudes from other children, remembering how she was beat up almost daily at school. Clearly, Levittown’s racist feelings had not disappeared. After several years, they chose to return to Philadelphia to a more predominately black neighborhood.

Civil rights were not only violated in the Deep South, where national news was being made over bombings, sit-ins, peaceful protests, and lynchings, but right here in the Philadelphia suburbs where families were simply trying to provide a home for their children. Segregation, discrimination and racism was blatant, ugly and violent in Pennsylvania, a state that was founded on Quaker ideals of freedom, tolerance, and passivism. As of the 2010 census, Levittown was 87.7% white and only 3.6% African American. Perhaps not much has changed over the past 60 years since the Myers family was brave enough to break through the “Whites Only” unwritten rule of Levittown.

Daisy Myers honored in 1999 when a tree was planted in her name and a formal apology given by the city (Trentonian)

Author’s note

Article originally begun in 2017 while an undergraduate student at Cedar Crest College. If you are interested in learning more about residential segregation in the Philadelphia area, and the role of federal agencies in maintaining segregated neighborhoods, I highly recommend The Color of Law, by Richard Rothstein and Up South, by Matthew J. Countryman.

References:

Bittan, David B. (August 19, 1958) “Ordeal in Levittown.” The Library of America. Retrieved from: http://storyoftheweek.loa.org/2016/01/ordeal-in-levittown.html on July 20, 2017.

Blumgart, Jake. (March 1, 2017) “What Will Become of Levittown, Pennsylvania?” City Lab. Retrieved from: https://www.citylab.com/equity/2016/03/what-will-become-of-levittown-pennsylvania/471438/ on July 20, 2017.

Brubaker, Jack. (November 27, 2007) “Lancastrian in 2nd Black Family to Move into Levittown.” Lancaster Online. Retrieved from: http://lancasteronline.com/opinion/lancastrian-in-nd-black-family-to-move-into-levittown/article_59a2be7f-4fb5-5499-92f1-bd2816850fd9.html on July 21, 2017.

Explore PA History Staff. “Behind the Marker – Levittown Historical Marker.” Explore PA History. Retrieved from: http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-3DD on July 18, 2017.

Kaplan, Erin Aubrey. (February 3, 2009) “Levittown by David Kushner.” Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from: http://articles.latimes.com/print/2009/feb/03/entertainment/et-book3 on July 18, 2017.

McCrary, Lacy. (August 21, 1997) “Trauma of Levittown integration remembered in History: In August 1957, an African American family moved to Deepgreen Lane and was greeted by a mob screaming racial epithets and making threats.” The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1997-08-21/news/1997233064_1_daisy-myers-levittown-epithets on July 21, 2017.

Parker, L.A. (December 10, 2011) “Daisy Myers was a touch of class in Levittown.” The Trentonian. Retrieved from: http://www.trentonian.com/article/TT/20111210/opinion/312109998 on July 18, 2017.

PHMC Staff. “Civil Rights and Integration in Levittown – August 1957.” Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved from: http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/documents/1946-1979/levittown.html on July 18, 2017.

Yardley, Jonathan. (February 15, 2009) “Jonathan Yardley on ‘Levittown’.” The Washington Post. Retrieved from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/02/12/AR2009021203324_pf.html on July 20, 2017.